We have officially started to tread the sacred grounds of human genetic modification. Few topics are as taboo as human embryo gene editing and it only took a tiny step forward to stir the pot of heavy criticism and controversy. Thanks to NPR’s report, we now have the name of the first researcher known to attempt to modify the genes of healthy human embryos. But the likelihood that progress in this area has already been made in private labs around the world is large.

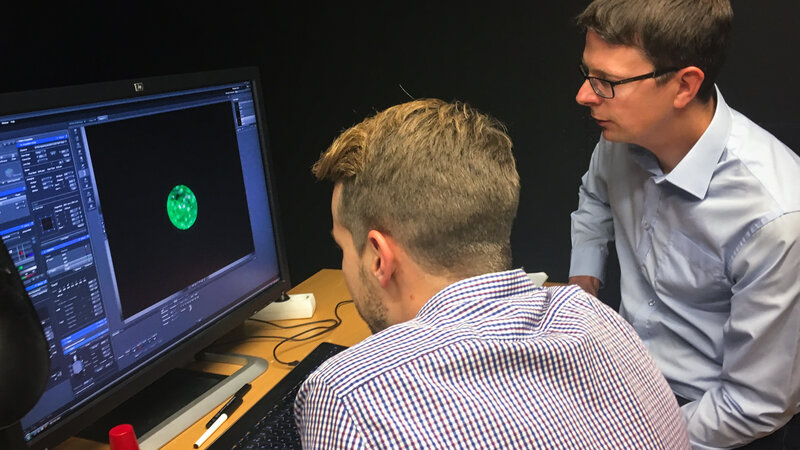

Fredrik Lanner (Karolinska Institute, Stockholm), a Swedish developmental biologist, is attempting to edit genes in human embryos to learn more about how the genes regulate early embryonic development. He has invited an NPR reporter to his lab and has given him a live demonstration of gene editing, becoming the first publicly acknowledged researcher conducting such experiments. Lanner’s hopes to apply the knowledge to treat infertility and prevent miscarriages, but what is locked behind the walls of human embryos could be useful in treating many diseases:

“If we can understand how these early cells are regulated in the actual embryo, this knowledge will help us in the future to treat patients with diabetes, or Parkinson, or different types of blindness and other diseases,” he says.

However, it is fair to say that arguments of those who are against genetic modification of human embryos are completely valid. Even if what Lanner is doing is not a direct cause for concern, it could open doors to potentially dangerous applications. The truly controversial one is to actually let the modified embryo fully develop. Think designer babies with parents being able to pick and choose their future child’s traits, but also the risk of accidentally introducing errors into the human gene pool. The size of the potential repercussions would be anyone’s guess – minor, catastrophic, or anything inbetween.

For that very reason, Lanner is planning to never let the embryos develop past 14 days. There is much to learn even in that narrow time frame.

Lanner and his team are using a genetic engineering tool known as CRISPR-Cas9 which comprises two molecules that can zero in on individual genes and make very precise changes to the DNA. It allows for unprecedented finesse in gene editing:

“It’s not just quicker or cheaper,” Lanner says. “This actually opens the door to start to look at this for the first time, because we could not do this at all previously in the human embryo. The technology was just not efficient enough to try to look at individual gene function as the embryo develops.”

CRISPR’s ease and precision have made the prospect of editing human embryos nearly inevitable, says Chad Cowan, a stem cell biologist at Harvard University. “Now that you can do that and garner considerable attention, it’s basically light to moths,” he says. “There will be certain people who will find it irresistible to do it whether it’s scientifically justified or not.” He also said that such experiments are probably already being performed privately in the United States, China, and other countries.

Lanner is planning to methodically knock out a series of genes that he has identified through previous work as being crucial to normal embryonic development. He hopes that will help him learn more about what the genes do and which ones cause infertility.

Lanner has now done this on at least a dozen embryos, but is still studying his results and refining his techniques. He remains unsure how well the editing is working so far. However, he’s confident he’ll be able to modify individual genes in the embryos to determine their function.

But we need to remind ourselves that even though Lanner’s work in and of itself is basic enough to be harmless, the avenues it opens are huge. While non-negligible amount of people have ethical objections – considering a human embryo to have the moral standing of a person, the Human Gene-Editing Initiative, launched by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, was reluctant to do anything but preliminarily accept Lanner’s work on the grounds of it being fundamental enough.

Not all expert organizations are quite as forgiving though. Marcy Darnovsky, the head of the Center for Genetics & Society, has voiced concerns over DNA editing, even if her organization is in favor of human embryonic research:

“The production of genetically modified human embryos is actually quite dangerous,” Darnovsky says. “It’s a step toward attempts to produce genetically modified human beings. This would be reason for grave concern. When you’re editing the genes of human embryos, that means you’re changing the genes of every cell in the bodies of every offspring, every future generation of that human being,” she says. “So these are permanent and probably irreversible changes that we just don’t know what they would mean.”

“If we’re going to be producing genetically modified babies, we are all too likely to find ourselves in a world where those babies are perceived to be biologically superior. And then we’re in a world of genetic haves and have-nots,” Darnovsky says. “That could lead to all sorts of social disasters. It’s not a world I want to live in.”

Whichever side of the fence you are on, the discussion is sure to heat up sooner or later. Some have predicted philosophical and ideological clashes with the rapid development of artificial intelligence and robotics, but if something could get a head start, it’s probably GMO humans.